blog

2023/11/03

Build a scalable, self-managed streaming infrastructure with Beam and FlinkTalat Uyarer

In this blog series, Talat Uyarer (Architect / Senior Principal Engineer), Rishabh Kedia (Principal Engineer), and David He (Engineering Director) describe how we built a self-managed streaming platform by using Apache Beam and Flink. In this part of the series, we describe why and how we built a large-scale, self-managed streaming infrastructure and services based on Flink by migrating from a cloud managed streaming service. We also outline the learnings for operational scalability and observability, performance, and cost effectiveness. We summarize techniques that we found useful in our journey.

Build a scalable, self-managed streaming infrastructure with Flink - part 1

Introduction

Palo Alto Networks (PANW) is a leader in cybersecurity, providing products, services and solutions to our customers. Data is the center of our products and services. We stream and store exabytes of data in our data lake, with near real-time ingestion, data transformation, data insertion to data store, and forwarding data to our internal ML-based systems and external SIEM’s. We support multi-tenancy in each component so that we can isolate tenants and provide optimal performance and SLA. Streaming processing plays a critical role in the pipelines.

In the second part of the series, we provide a more thorough description of the core building blocks of our streaming infrastructure, such as autoscaler. We also give more details about our customizations, which enabled us to build a high-performance, large-scale streaming system. Finally, we explain how we solved challenging problems.

The importance of self-managed streaming Infrastructure

We built a large-scale data platform on Google Cloud. We used Dataflow as a managed streaming service. With Dataflow, we used the streaming engine running our application using Apache Beam and observability tools such as Cloud Logging and Cloud Monitoring. For more details, see [1]. The system can handle 15 million of events per second and one trillion events daily, at four petabytes of data volume daily. We run about 30,000 Dataflow jobs. Each job can have one or hundreds of workers, depending on the customer’s event throughputs.

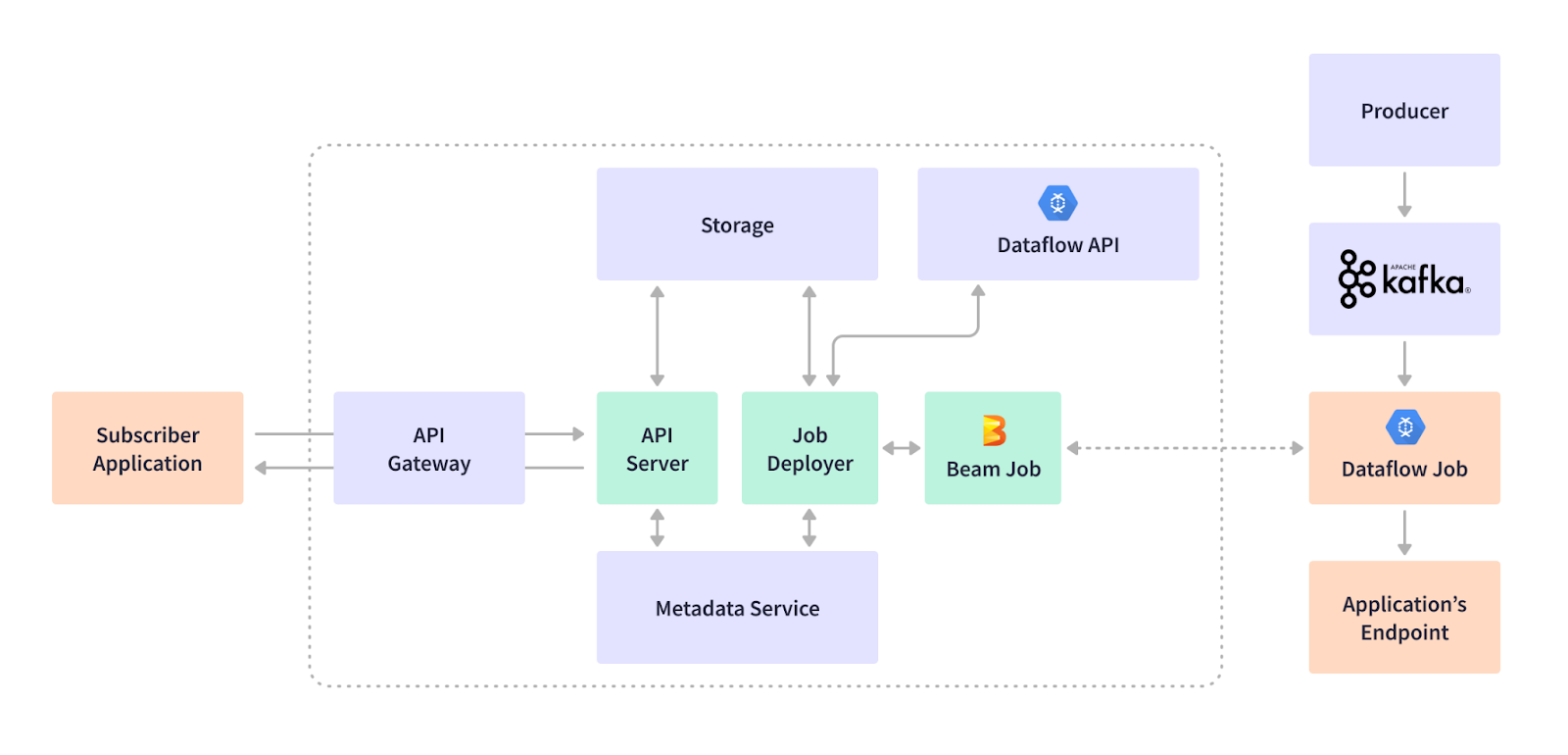

We support various applications using different endpoints: BigQuery data store, HTTPS-based external SIEMs or internal endpoints, Syslog based SIEMs, and Google Cloud Storage endpoints. Our customers and products rely on this data platform to handle cybersecurity postures and reactions. Our streaming infrastructure is highly flexible to add, update, and delete use cases through a streaming job subscription. For example, a customer wants to ingest log events from a firewall device into the data lake buffered in Kafka topics. A streaming job is subscribed to extract and filter the data, transform the data format, and do a streaming insert to our BigQuery data warehouse endpoint in real-time. The customer can use our visualization and dashboard products to view traffic or threads captured by this firewall. The following diagram illustrates the event producer, the use case subscription workflow, and the key components of the streaming platform:

This managed, Dataflow-based streaming infrastructure runs fine, but with some caveats:

- Cost is high, because it is a managed service. For the same resources used in a Dataflow application, such as vCPU and memory, the cost is much more expensive than using an open source streaming engine such as Flink running the same Beam application code.

- It’s not easy to achieve our latency and SLA goals, because it’s difficult to extend features, such as autoscaling based on different applications, endpoints, or different parameters within one application.

- The pipeline only runs on Google Cloud.

The uniqueness of PANW’s streaming use cases is another reason that we use a self-managed service. We support multi-tenancy. A tenant (a customer) can ingest data at a very high rate (>100k requests per second), or at a very low rate (< 100 requests per second). A Dataflow job runs on VMs instead of Kubernetes, requiring a minimal one vCPU core. With a small tenant, this wastes resources. Our streaming infrastructure supports thousands of jobs, and the CPU utilization is more efficient if we do not have to use one core for a job. It is natural for us to use a streaming engine running on Kubernetes, so that we can allocate minimal resources for a small tenant, for example, using a Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE) pod with ½ or less vCPU core.

The choice of Apache Flink and Kubernetes

In an effort to handle the problems already stated and to find the most efficient solution, we evaluated various streaming frameworks, including Apache Samza, Apache Flink, and Apache Spark, against Dataflow.

Performance

- One notable factor was Apache Flink’s native Kubernetes support. Unlike Samza, which lacked native Kubernetes support and required Apache Zookeeper for coordination, Flink seamlessly integrated with Kubernetes. This integration eliminated unnecessary complexities. In terms of performance, both Samza and Flink were close competitors.

- Apache Spark, while popular, proved to be significantly slower in our tests. A presentation at the Beam Summit revealed that Apache Beam’s Spark Runner was approximately ten times slower than Native Apache Spark [3]. We could not afford such a drastic performance hit. Rewriting our entire Beam codebase with native Spark was not a viable option, especially given the extensive codebase we had built over the past four years with Apache Beam.

Community

The robustness of community support played a pivotal role in our decision making. Dataflow provided excellent support, but we needed assurance in our choice of an open-source framework. Apache Flink’s vibrant community and active contributions from multiple companies offered a level of confidence that was unmatched. This collaborative environment meant that bug identification and fixes were ongoing processes. In fact, in our journey, we have patched our system using many Flink fixes from the community:

- We fixed the Google Cloud Storage file reading exceptions by merging Flink 1.15 open source fix FLINK-26063 (we are using 1.13).

- We fixed an issue with workers restarting for stateful jobs from FLINK-31963.

We also contributed to the community during our journey by founding and fixing bugs in the open source code. For details, see FLINK-32700 for Flink Kubernetes Operator. We also created a new GKE Auth support for Kubernetes clients and merged it to GitHub at [4].

Integration

The seamless integration of Apache Flink with Kubernetes provided us with a flexible and scalable platform for orchestration. The synergy between Apache Flink and Kubernetes not only optimized our data processing workflows but also future-proofed our system.

Architecture and deployment workflow

In the realm of real-time data processing and analytics, Apache Flink distinguishes itself as a powerful and versatile framework. When combined with Kubernetes, the industry-standard container orchestration system, Flink applications can scale horizontally and have robust management capabilities. We explore a cutting-edge design where Apache Flink and Kubernetes synergize seamlessly, thanks to the Apache Flink Kubernetes Operator.

At its core, the Flink Kubernetes Operator serves as a control plane, mirroring the knowledge and actions of a human operator managing Flink deployments. Unlike traditional methods, the Operator automates critical activities, from starting and stopping applications to handling upgrades and errors. Its versatile feature set includes fully-automated job lifecycle management, support for different Flink versions, and multiple deployment modes, such as application clusters and session jobs. Moreover, the Operator’s operational prowess extends to metrics, logging, and even dynamic scaling by using the Job Autoscaler.

Build a seamless deployment workflow

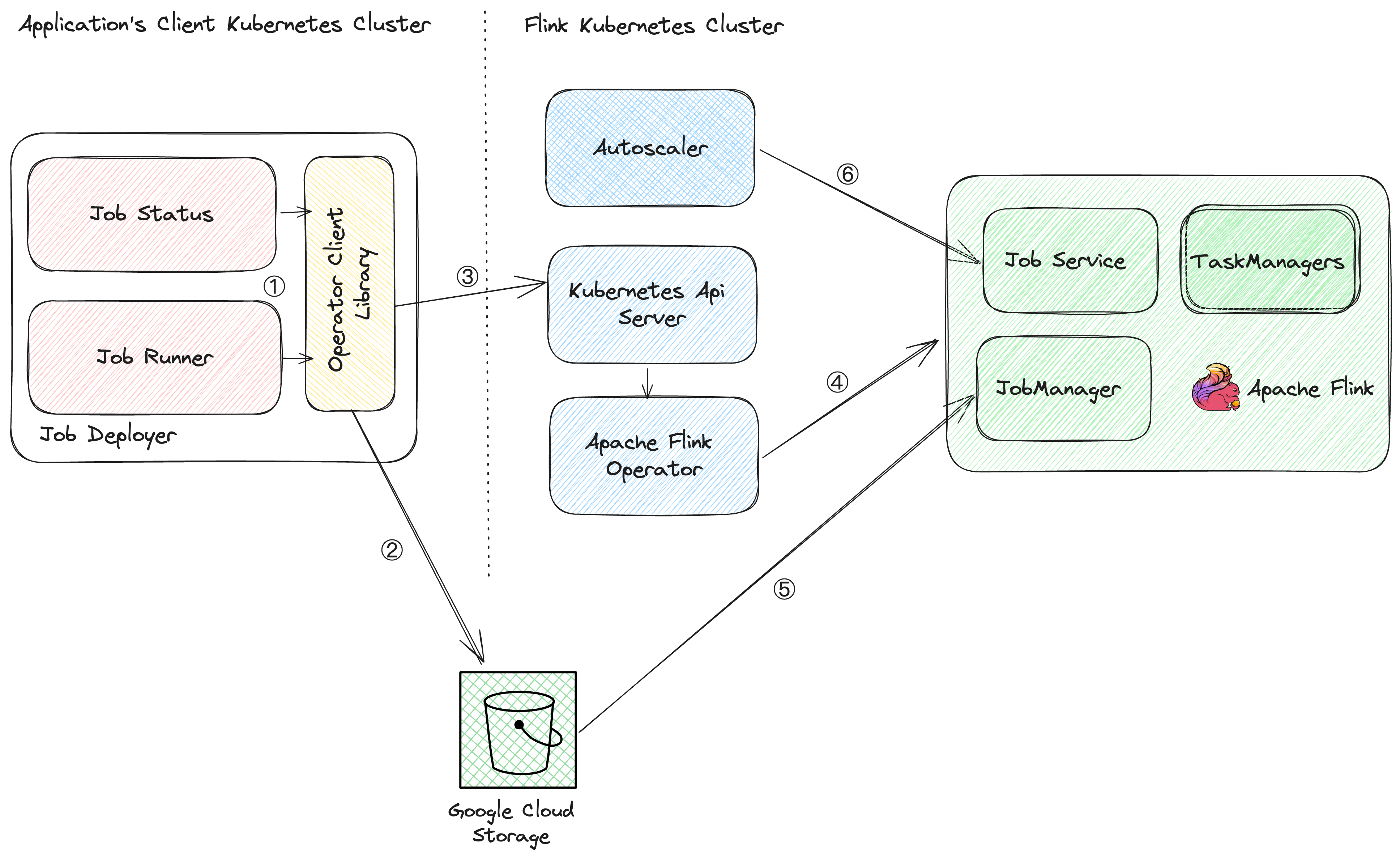

Imagine a robust system where Flink jobs are deployed effortlessly, monitored diligently, and managed proactively. Our team created this workflow by integrating Apache Flink, Apache Flink Kubernetes Operator, and Kubernetes. Central to this setup is our custom-built Apache Flink Kubernetes Operator Client Library. This library acts as a bridge, enabling atomic operations such as starting, stopping, updating, and canceling Flink jobs.

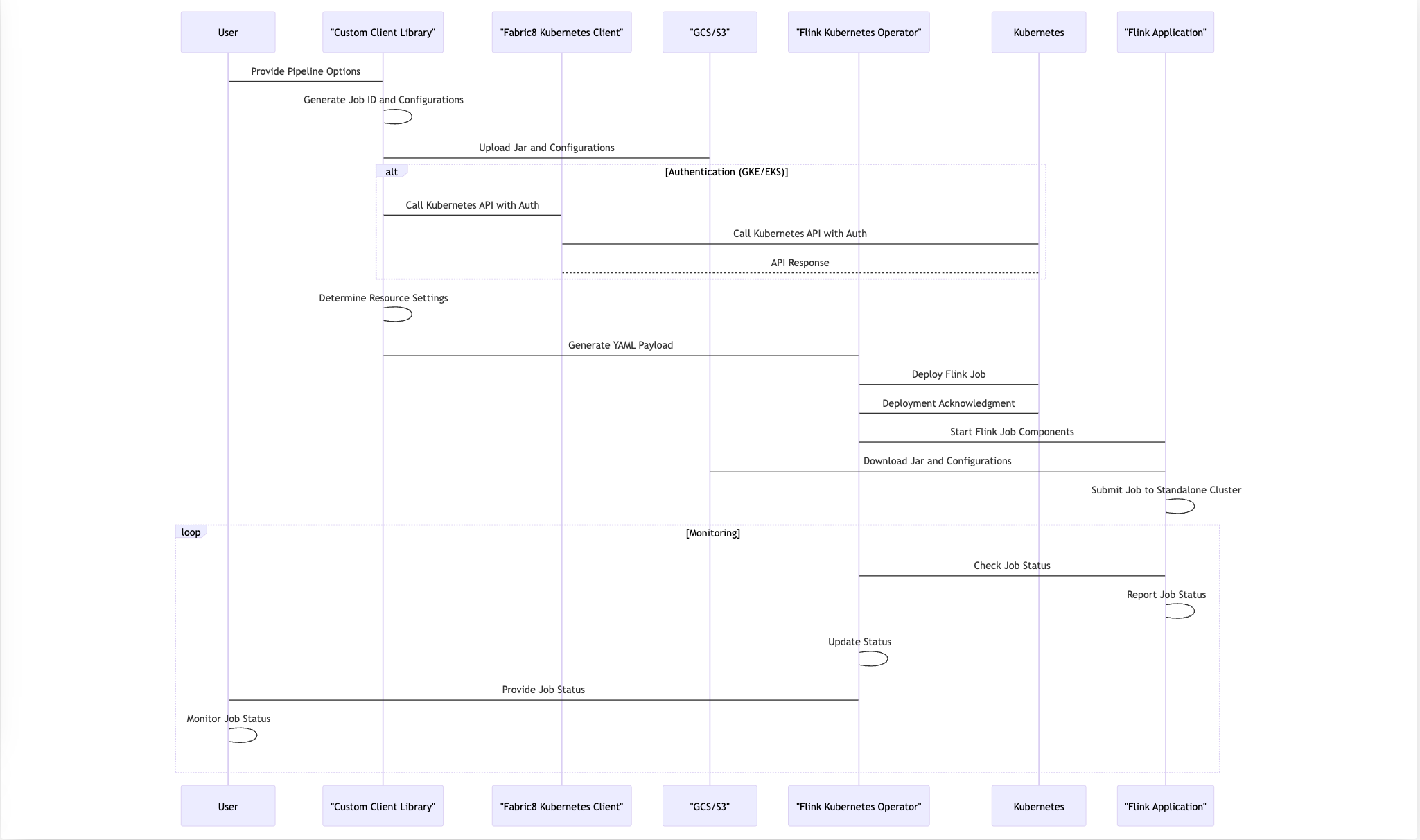

The deployment process

In our code, the client provides Apache Beam pipeline options, which include essential information such as the Kubernetes cluster’s API endpoint, authentication details, the Google Cloud/S3 temporary location for uploading the JAR file, and worker type specifications. The Kubernetes Operator Library uses this information to orchestrate a seamless deployment process. The following sections explain the steps taken. Most of the core steps are automated in our code base.

Step 1:

- The client wants to start a job for a customer and a specific application.

Step 2:

- Generate a unique job ID: The library generates a unique job ID, which is set as a Kubernetes label. This identifier helps track and manage the deployed Flink job.

- Configuration and code upload: The library uploads all necessary configurations and user code to a designated location on Google Cloud Storage or Amazon S3. This step ensures that the Flink application’s resources are available for deployment.

- YAML payload generation: After the upload process completes, the library constructs a YAML payload. This payload contains crucial deployment information, including resource settings based on the specified worker type.

We used a convention for naming our worker VM instance types. Our convention is similar to the naming convention that Google Cloud uses. The name n1-standard-1 refers to a specific, predefined VM machine type. Let’s break down what each component of the name means:

- n1 indicates the CPU type of the instance. In this case, it refers to the Intel based on instances in the N1 series. Google Cloud has multiple generations of instances with varying hardware and performance characteristics.

- standard signifies the machine type family. Standard machine types offer a balanced ratio of 1 virtual CPU (vCPUs) and 4 GB of memory for Task Manager, and 0.5 vCPU and 2 GB memory for Job Manager.

- 1 represents the number of vCPUs available in the instance. In the case of n1-standard-1, it means the instance has 1 vCPU.

Step 3:

- Calling the Kubernetes API with Fabric8: To initiate the deployment, the library interacts with the Kubernetes API using Fabric8. Fabric8 initially lacked support for authentication in Google Kubernetes Engine or Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS). To address this limitation, our team implemented the necessary authentication support, which can be found in our merge request on GitHub PR [4].

Step 4:

- Flink Operator deployment: When it receives the YAML payload, the Flink Operator takes charge of deploying the various components of the Flink job. Tasks include provisioning resources and managing the deployment of the Flink Job Manager, Task Manager, and Job Service.

Step 5:

- Job submission and execution: When the Flink Job Manager is running, it fetches the JAR file and configurations from the designated Google Cloud Storage or S3 location. With all necessary resources in place, it submits the Flink job to the standalone Flink cluster for execution.

Step 6

- Continuous monitoring: Post-deployment, our operator continuously monitors the status of the running Flink job. This real-time feedback loop enables us to promptly address any issues that arise, ensuring the overall health and optimal performance of our Flink applications.

In summary, our deployment process leverages Apache Beam pipeline options, integrates seamlessly with Kubernetes and the Flink Operator, and employs custom logic to handle configuration uploads and authentication. This end-to-end workflow ensures a reliable and efficient deployment of Flink applications in Kubernetes clusters while maintaining vigilant monitoring for smooth operation. The following sequence diagram shows the steps.

Develope an autoscaler

Having an autoscaler is critical to having a self-managed streaming service. There are not enough resources available on the internet for us to learn to build our own autoscaler, which makes this part of the workflow difficult.

The autoscaler scales up the number of task managers to drain the lag and to keep up with the throughput. It also scales down the minimum number of resources required to process the incoming traffic to reduce costs. We need to do this frequently while keeping the processing disruption to minimum.

We extensively tuned the autoscaler to meet the SLA for latency. This tuning involved a cost trade off. We also made the autoscaler application-specific to meet specific needs for certain applications. Every decision has a hidden cost. The second part of this blog provides more details about the autoscaler.

Create a client library for steaming job development

To deploy the job using the Flink Kubernetes Operator, you need to know about how Kubernetes works. The following steps explain how to create a single Flink job.

- Define a YAML file with proper specifications. The following image provides an example.

apiVersion: flink.apache.org/v1beta1

kind: FlinkDeployment

metadata:

name: basic-reactive-example

spec:

image: flink:1.13

flinkVersion: v1_13

flinkConfiguration:

scheduler-mode: REACTIVE

taskmanager.numberOfTaskSlots: "2"

state.savepoints.dir: file:///flink-data/savepoints

state.checkpoints.dir: file:///flink-data/checkpoints

high-availability: org.apache.flink.kubernetes.highavailability.KubernetesHaServicesFactory

high-availability.storageDir: file:///flink-data/ha

serviceAccount: flink

jobManager:

resource:

memory: "2048m"

cpu: 1

taskManager:

resource:

memory: "2048m"

cpu: 1

podTemplate:

spec:

containers:

- name: flink-main-container

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /flink-data

name: flink-volume

volumes:

- name: flink-volume

hostPath:

# directory location on host

path: /tmp/flink

# this field is optional

type: Directory

job:

jarURI: local:///opt/flink/examples/streaming/StateMachineExample.jar

parallelism: 2

upgradeMode: savepoint

state: running

savepointTriggerNonce: 0

mode: standalone

- SSH into your Flink cluster and run the command following command:

kubectl create -f job1.yaml

- Use the following command to check the status of the job:

kubectl get flinkdeployment job1

This process impacts our scalability. Because we frequently update our jobs, we can’t manually follow these steps for every running job. To do so would be highly error prone and time consuming. One wrong space in the YAML can fail the deployment. This approach also acts as a barrier to innovation, because you need to know Kubernetes to interact with Flink jobs.

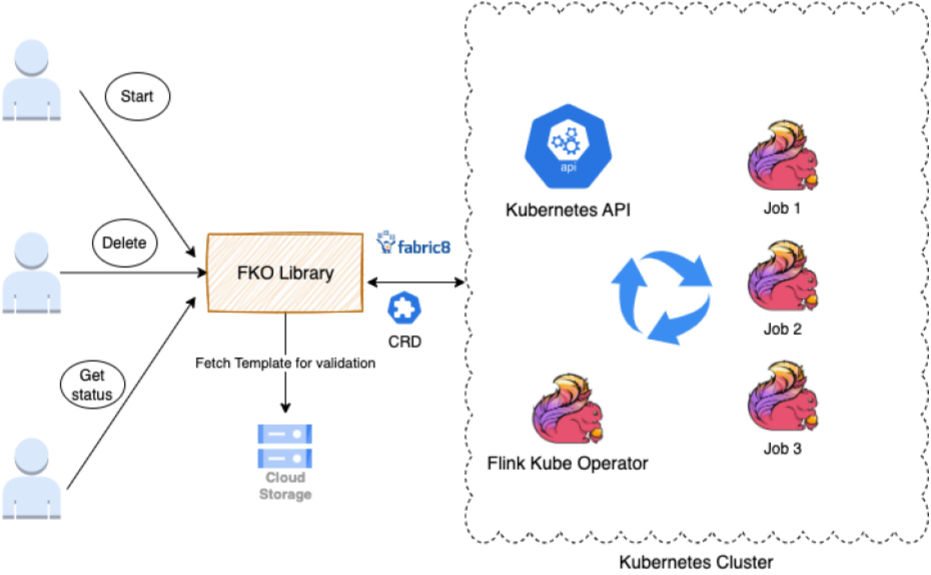

We built a library to provide an interface for any teams and applications that want to to start, delete, update, or get the status of their jobs.

This library extends the Fabric8 client and FlinkDeployment CRD. FlinkDeployment CRD is exposed by the Flink Kubernetes Operator. CRD lets you store and retrieve structured data. By extending the CRD, we get access to POJO, making it easier to manipulate the YAML file.

The library supports the following tasks:

- Authentication to ensure that you are allowed to perform actions on the Flink cluster.

- Validation (fetches the template from AWS/Google Cloud Storage for validation) takes user variable input and validates it against the policy, rules, YAML format.

- Action execution converts the Java call to invoke the Kubernetes operation.

During this process, we learned the following lessons:

- App specific operator service: At our large scale, the operator was unable to handle such a large number of jobs. Kubernetes calls started to time out and fail. To solve this problem, we created multiple operators (about 4) in high-traffic regions to handle each application.

- Kube call caching: To prevent overloading, we cached the results of Kubernetes calls for thirty to sixty seconds.

- Label support: Providing label support to search jobs using client-specific variables reduced the load on Kube and improved the job search speed by 5x.

The following are some of the biggest wins we achieved by exposing the library:

- Standardized job management: Users can start, delete, and get status updates for their Flink jobs in a Kubernetes environment using a single library.

- Abstracted Kubernetes complexity: Teams no longer need to worry about the inner workings of Kubernetes or the formatting job deployment YAML files. The library handles these details internally.

- Simplified upgrades: With the underlying Kubernetes infrastructure, the library brings robustness and fault tolerance to Flink job management, ensuring minimal downtime and efficient recovery.

Observability and alerting

Observability is important when runing a production system at a large scale. We have about 30,000 streaming jobs in PANW. Each job serves a customer for a specific application. Each job also reads data from multiple topics in Kafka, performs transformations, and then writes the data to various sinks and endpoints.

Constraints can occur anywhere in the pipeline or its endpoints, such as the customer API, BigQuery, and so on. We want to make sure the latency of streaming meets the SLA. Therefore, understanding if a job is healthy, meeting SLA, and alerting and intervening when needed is very challenging.

To achieve our operational goals, we built a sophisticated observability and alerting capability. We provide three kinds of observability and debugging tools, described in the following sections.

Flink job list and job insights from Prometheus and Grafana

Each Flink job sends various metrics to our Prometheus with cardinality details, such as application name, customer Id, and regions, so that we can look at each job. Critical metrics include the input traffic rate, output throughput, backlogs in Kafka, timestamp-based latency, task CPU usage, task numbers, OOM counts, and so on.

The following charts provide a few examples. The charts provide details about the ingestion traffic rate to Kafka for a specific customer, the streaming job’s overall throughput, each vCPU’s throughput, backlogs in Kafka, and worker autoscaling based on the observed backlog.

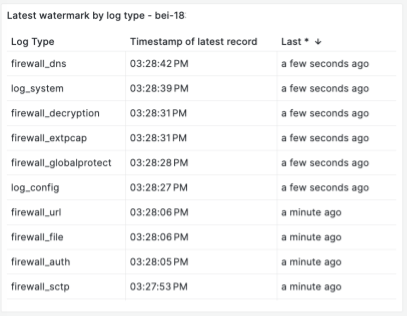

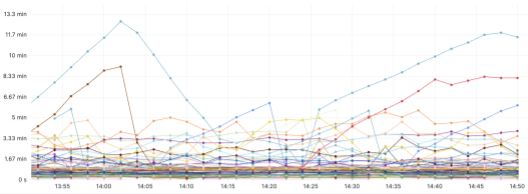

The following chart shows streaming latency based on the timestamp watermark. In addition to the numbers of events in Kafka as backlogs, it is important to know the time latency for end-to-end streaming so that we can define and monitor the SLA. The latency is defined as the time taken for the streaming processing, starting from ingestion timestamp, to the timestamp sending to the streaming endpoint. A watermark is the last processed event’s time. With the watermark, we are tracking P100 latency. We track each event’s stream latency, so that we can understand each Kafka topic and partition or Flink job pipeline issue. The following example shows each event stream and its latency:

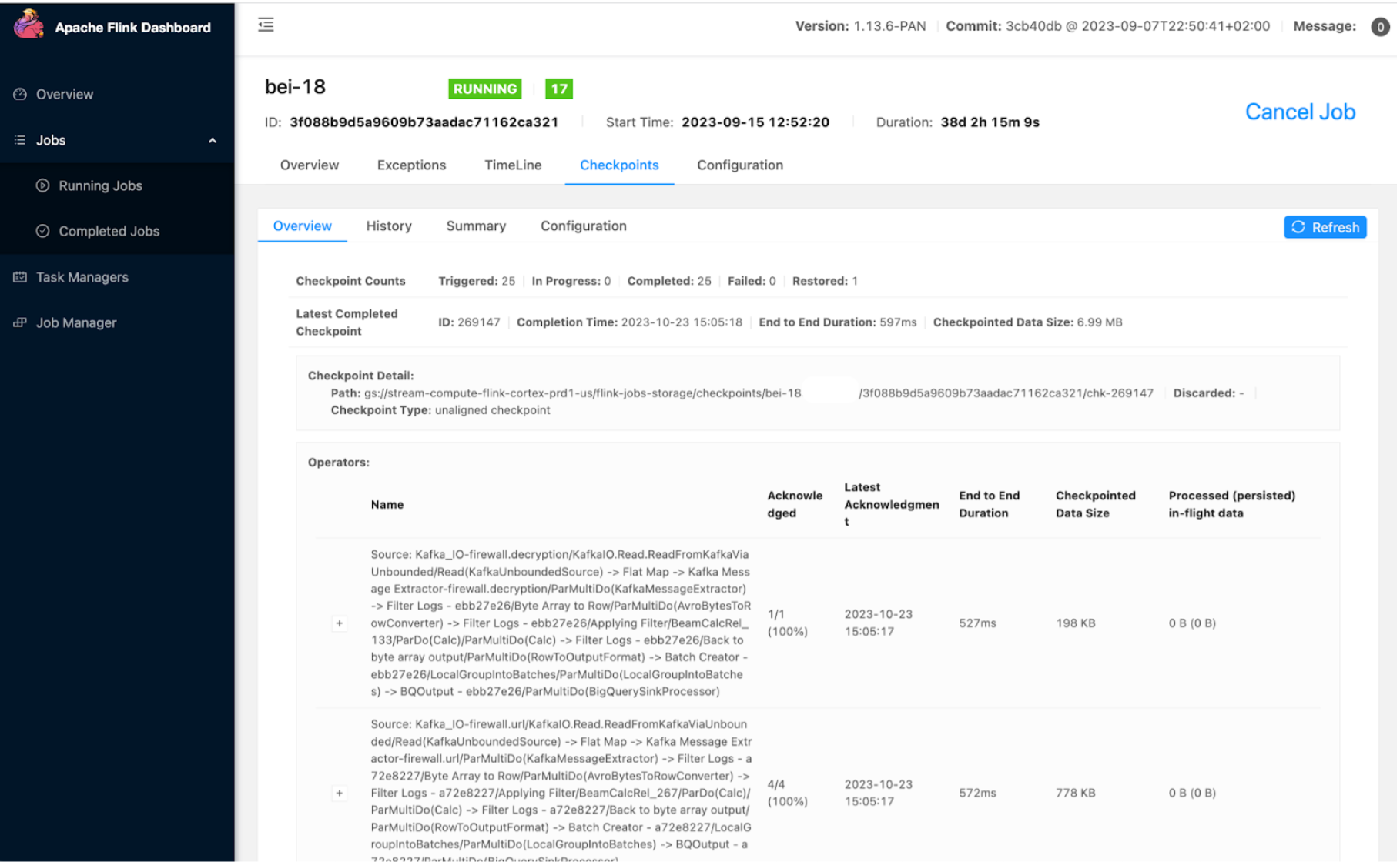

Flink open source UI

We use and extend the Apache Flink dashboard UI to monitor jobs and tasks, such as the checkpoint duration, size, and failure. One important extension we used is a job history page that lets us see a job’s start and update timeline and details, which helps us to debug issues.

Dashboards and alerting for backlog and latency

We have about 30,000 jobs, and we want to closely monitor the jobs and receive alerts for jobs in abnormal states so that we can intervene. We created dashboards for each application so that we can show the list of jobs with the highest latency and create thresholds for alerts. The following example shows the timestamp-based latency dashboard for one application. We can set the alerting if the latency is larger than a threshold, such as 10 minutes, for a certain time continuously:

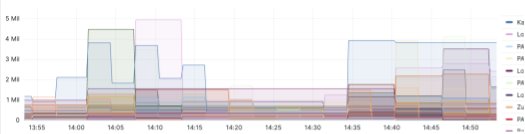

The following example shows more backlog-based dashboards:

The alerts are based on thresholds, and we frequently check metrics. If a threshold is met and continues for a certain amount of times, we alert our internal Slack channels or PagerDuty for immediate attention. We tune the alerting so that the accuracy is high.

Cost optimization strategies and tuning

We also moved to a self-managed streaming service to improve cost efficiency. Several minor tunings have allowed us to reduce costs by half, and we have more opportunities for improvement.

The following list includes a few tips that have helped us:

- Use Google Cloud Storage as checkpointing storage.

- Reduce the write frequency to Google Cloud Storage.

- Use appropriate machine types. For example, in Google Cloud, N2D machines are 15% less expensive than N2 machines.

- Autoscale tasks to use optimal resources while maintaining the latency SLA.

The following sections provide more details about the first two tips.

Google Cloud Storage and checkpointing

We use Google Cloud Storage as our checkpoint store because it is cost-effective, scalable, and durable. When working with Google Cloud Storage, the following design considerations and best practices can help you optimize scaling and performance:

- Use data partitioning methods like range partitioning, which divides data based on specific attributes, and hash partitioning, which distributes data evenly using hash functions.

- Avoid sequential key names, especially timestamps, to avoid hotspots and uneven data distribution. Instead, introduce random prefixes for object distribution.

- Use a hierarchical folder structure to improve data management and reduce the number of objects in a single directory.

- Combine small files into larger ones to improve read throughput. Minimizing the number of small files reduces inefficient storage use and metadata operations.

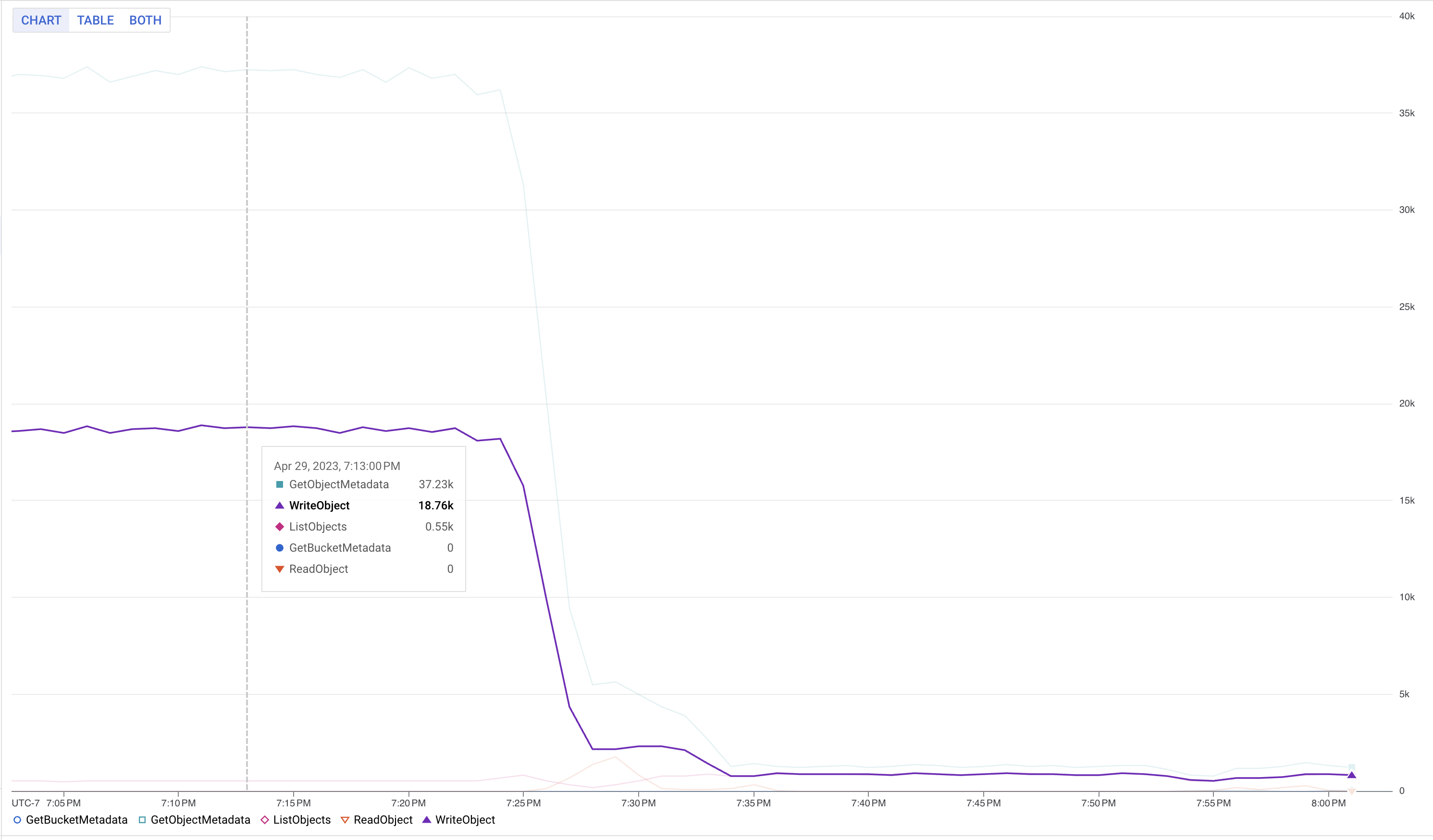

Tune the frequency of writing to Google Cloud Storage

Scaling jobs efficiently was one of our primary challenges. Stateless jobs, which are relatively simpler, still present hurdles, especially in scenarios where Flink needed to process an overwhelming number of workers. To overcome this challenge, We increased the state.storage.fs.memory-threshold settings to 1 MB from 20KB (??). This configuration allowed us to combine small checkpoint files into larger ones at the Job Manager level and to reduce metadata calls.

Optimizing the performance of Google Cloud operations was another challenge. Although Google Cloud Storage is excellent for streaming large amounts of data, it has limitations when it comes to handling high-frequency I/O requests. To mitigate this issue, we introduced random prefixes in key names, avoided sequential key names, and optimized our Google Cloud Storage sharding techniques. These methods significantly enhanced our Google Cloud Storage performance, enabling the smooth operation of our stateless jobs.

The following chart shows the Google Cloud Storage writes reduction after changing the memory-threshold:

Conclusion

Palo Alto Networks® Cortex Data Lake is fully migrated from Dataflow streaming engine to Flink self managed streaming engine infrastructure. We have achieved our goals to run the system more cost efficiently (more than half cost cut), and run the infrastructure on multiple clouds such as GCP and AWS. We have learned how to build a large scale reliable production system based on open sources. We see large potentials to customize the system based on our specific needs as we have a lot of freedom to customize the open source code and configuration. In the next Part 2 post we will give more details on autoscaling and performance tuning parts. We hope our experience will be helpful for readers who will explore similar solutions for their own organizations.

Additional Resources

We provide links here for related presentations as further reading for readers interested in implementing similar solutions. By adding this section, we hope you can find more details to build a fully managed streaming infrastructure, making it easier for readers to follow our stories and learnings.

[1] Streaming framework at PANW published at Apache Beam: https://beam.apache.org/case-studies/paloalto/

[2] PANW presentation at Beam Summit 2023: https://youtu.be/IsGW8IU3NfA?feature=shared

[3] Benchmark presented at Beam Summit 2021: https://2021.beamsummit.org/sessions/tpc-ds-and-apache-beam/

[4] PANW open source contribution to Flink for GKE Auth support: https://github.com/fabric8io/kubernetes-client/pull/4185

Acknowledgements

This is a large effort to build the new infrastructure and to migrate the large customer based applications from cloud provider managed streaming infrastructure to self-managed Flink based infrastructure at scale. Thanks the Palo Alto Networks CDL streaming team who helped to make this happen: Kishore Pola, Andrew Park, Hemant Kumar, Manan Mangal, Helen Jiang, Mandy Wang, Praveen Kumar Pasupuleti, JM Teo, Rishabh Kedia, Talat Uyarer, Naitk Dani, and David He.